by Carl Mayer, Director, Integrated Media/Active Entertainment

As we enter our third year of living in a world with Covid, it’s clear that just about every industry has been affected in some way. It’s equally clear that one of the most upheaved has been the entertainment industry, which had to change its exhibition model in response to a new set of realities.

Prior to 2020, theatrical releases followed a standard trend: debut as widely as possible, then see the number of screens decrease in time. The first week typically fared the best, and then things began to decline as the film aged and new titles came in to take its place.

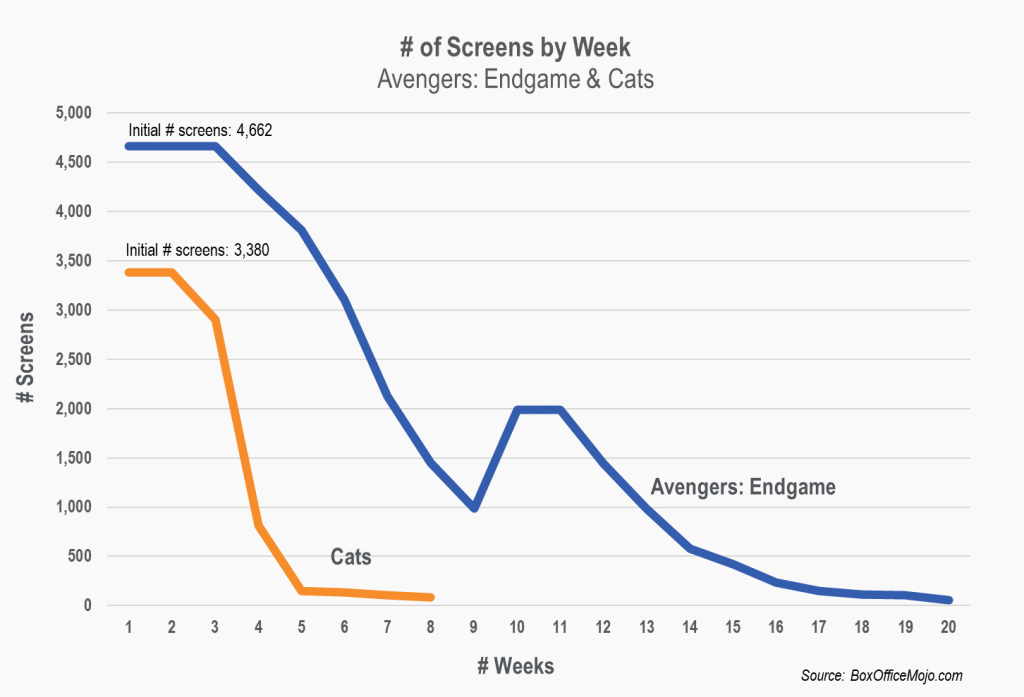

This trend was pretty consistent across the gamut of releases. Whether you’re you were the highest-grossing superhero film in history (Avengers: Endgame, which held onto the #1 spot for three weeks) or a notorious bomb (Cats, which debuted in fifth place), the pattern was the same:

Tony Stark et al stuck around for 20 weeks, while the Weber adaptation was little more than a “Memory” [forgive me] in eight. However, they both followed the same trend, notwithstanding a July 4 bump for Endgame. For decades, this has been the typical lifecycle for a theatrical release. (Strategically slow roll-outs like Parasite (2019) and The King’s Speech (2011) are of course exceptions.)

Historically, this trend was brought about by two main factors. First, audiences would turn out in their highest numbers during the first week or two of a film’s release. After that, pretty much everyone who was going to see it in a theater had seen it, and turnout began to wane—rapidly in some cases, more gradually in others.

Second, there had been a steady stream of releases, with the next potential blockbuster always waiting in the wings. Endgame was unseated by John Wick 3, which was usurped by the live-action Aladdin a week later. Aladdin was dethroned by The Secret Life of Pets 2, which was toppled by Men in Black: International and so on.

FEWER RELEASES

Both of those patterns have changed in the wake of the pandemic. Recall its early days, when there were no major productions in theaters: During the week of March 27, 2020 (film weeks begin on Fridays) Box Office Mojo reported three titles. The number-one film that week grossed $2,802.

As 2020 progressed and the situation improved, studios began rolling out films, but that slate had to be augmented with re-releases like The Empire Strikes Back and 1993’s Hocus Pocus.

Now, here we are in 2022 and while there is certainly a more robust release schedule (some of which had been shelved for two years), we still have nowhere near the kind of slate we’d seen in the past. This year, the week of March 4 saw 47 films in release; the comparable week in 2019 had 111 titles.

Multiplexes need to project something and with fewer films in the pipeline, releases stay in theaters longer than they ordinarily would. Sometimes, screens are even added well into a film’s run.

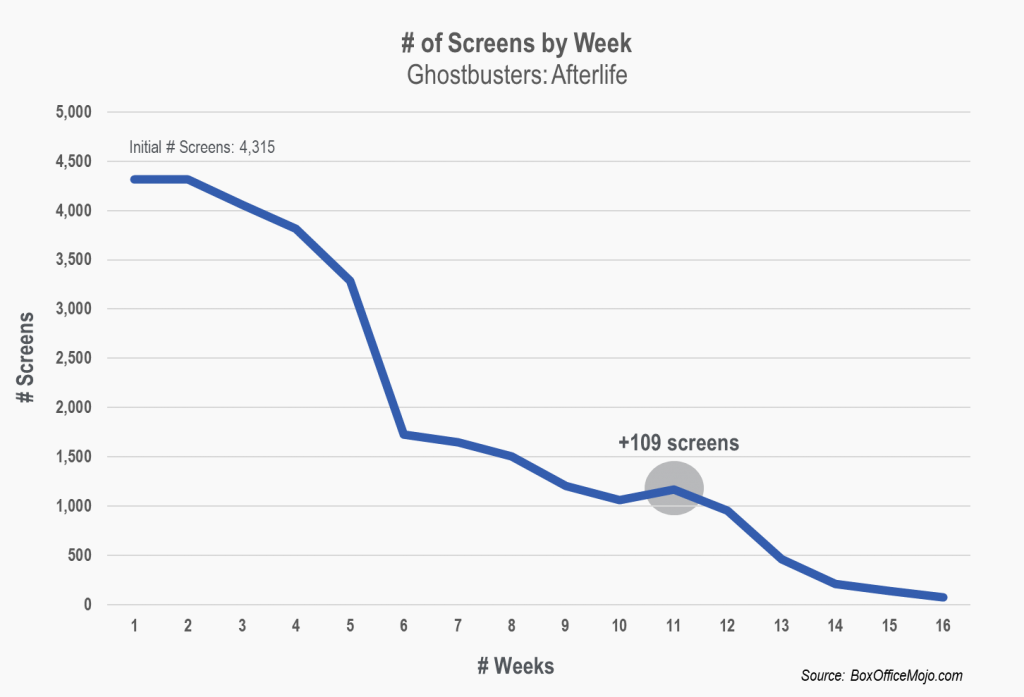

Take 2021’s Ghostbusters: Afterlife, for instance:

Ghost Busters: Afterlife, the third Ghostbusters film (not including the 2016 reboot) got a lukewarm reception from professional critics, though audiences had a much more positive reaction. It opened at number one, but its box office dropped 55% in its second week, putting it at number two. By week ten it was in 13th place and it seemed to be all but over. And yet in its 11th week, 109 screens were added and the film moved back up to number eight. All of this even though Afterlife had been available as a Premium VOD (around $20) rental for nearly a month and became available as a regular VOD rental or purchase that very week. The film has now completed its theatrical run, having lasted for 16 weeks.

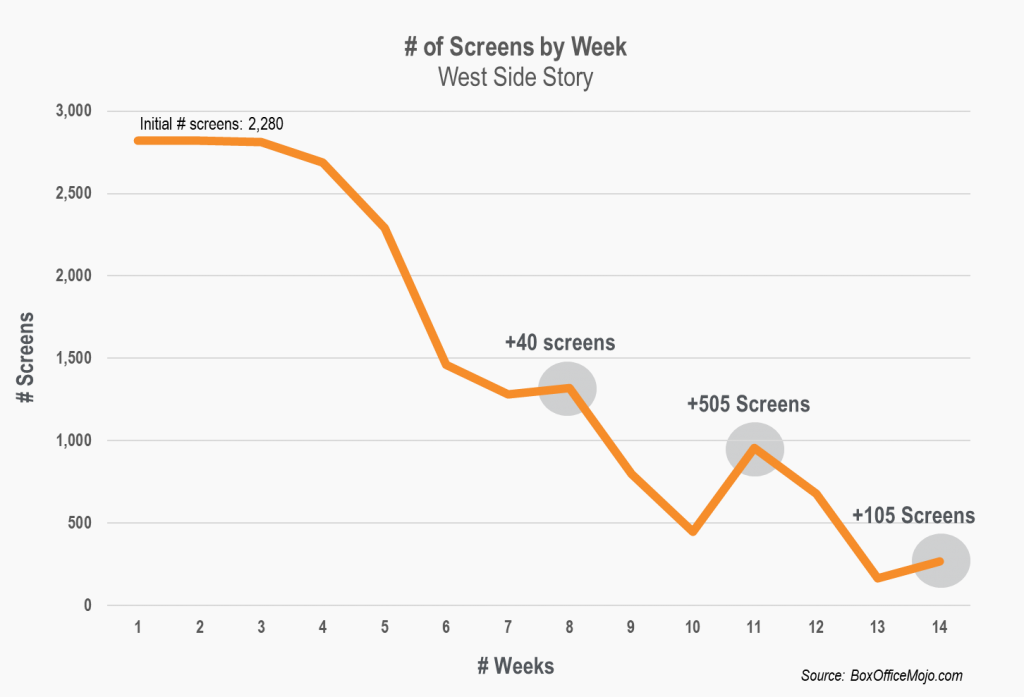

This phenomenon isn’t limited to franchise pictures: Steven Spielberg’s commercially disappointing take on West Side Story, which opened at number one before dropping to fifth place in week two, saw a 40-screen uptick in week eight, which helped keep it in the top ten. Then, in week 11 it added 505 screens—no doubt due to its seven Oscar nominations, but by this point it was only days away from availability on Disney+ and would ordinarily have been gone. In week 14, it got another 110-screen infusion of life.

CHANGING BEHAVIOR

It’s no longer about reluctance to return to theaters; the latest Spider-Man and Batman films have shown that people will turn out in droves if there’s something they want to see immediately. But for most movies, audiences are perfectly happy to see a movie later into its run. Exhibitors will keep films playing longer, as long as that behavior holds. If people come, the movie will stay in theaters. If the movie is in theaters, people will come.

I’m not suggesting that opening at number one doesn’t mean anything. A strong debut brings media attention and makes a film part of the pop culture conversation. What I am saying is that not having a huge opening is no longer fatal.

Obviously, this wasn’t a strategy that exhibitors had planned on. It was borne of necessity, an adaptation to the reality they were handed. As Covid becomes endemic and big releases become more frequent, things will start to get closer to the “old normal.” But should things really return to where they were before?

The old paradigm would never have lasted anyway—Covid just accelerated the change. Too many films were getting lost in the shuffle, not turning a profit or making less profit than they could have. If studios and theater chains permanently adopt elements of what they’ve been doing for the past two years—namely, fewer theatrically-released films than before, with longer stays in theaters—they’ll be better positioned for success moving forward.